- Home

- S. D. Perry

Cloak

Cloak Read online

Thank you for purchasing this Pocket Books eBook.

* * *

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Pocket Books and Simon & Schuster.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Content

Acknowledgement

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Epilogue

For the writers of the original series, who made history

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A few of the people who helped to make this book possible are: Dr. Joelle Murray, my only science-savvy friend, whose facts I keep messing with; Mÿk Olsen, my husband, who keeps me sane, for the most part; Michael and Denise Okuda, for the brilliant encyclopedia and chronology, which kept me from drowning; and Marco Palmieri, my editor, who deserves most of the credit for this novel’s outline, and a vacation.

Together let us beat this ample field,

Try what the open, what the covert yield.

—ALEXANDER POPE

Prologue

Jack Casden was having a nightmare, one he couldn’t wake from because he wasn’t asleep. Alone on the bridge, cut off from the rest of the ship, nothing responding to his commands—the only thing missing from this particular bad dream was some slithering and evil monster, although Casden was quite aware that monsters came in many forms, some of them as human as he was. To complete his nightmare, the incrementally rising, reedy whine of the warp engines humming through the walls and floor told him that it wouldn’t be long now, not long at all. An hour, give or take. He’d be dead by then, anyway.

Casden took a deep breath, yet another in a series of deep breaths that wouldn’t sustain him much longer, that barely sustained him now. No one was answering their communicators anymore, his last contact forty minutes before, with a dying ensign who was locked in her quarters. The very thought of it made him sick and weary, though he had no doubt he’d be sleeping soon enough, and for eternity; the only question was which would hold out longer, the air or the ship herself.

Was it worth it? Worth losing everything, just to die alone in the middle of nowhere?

There wasn’t an answer; the question as futile as his situation. If he’d seen it coming, if he hadn’t acted so rashly, if he’d given some thought to politics earlier in his career . . . worrying about what he might have done to make things different was useless in the here and now, it only worked to stoke the fires of his panic, and his self-control was all he had left. Everything else—his ship, his crew, his reputation—was gone, lost to his mistakes and those men and women who had exploited them.

Desperate, Casden held himself tighter against the growing cold, returning to theories and plans that he’d already rejected as impossible, sorting through them just to reject them again; short of giving up, it was all he could do. The ship’s computer wouldn’t answer, all bridge controls were locked out and unresponsive, and the subspace communications arrays had been damaged beyond repair. Even if he could find a way to record what was happening, to somehow explain himself, the ship was at warp five or six already and rising, he could tell by the sound; he figured she would blow up before she shook apart, and either way, there would be nothing left of her.

The bridge life-support had been cut last; his crew was surely dead. He didn’t want to think about it, didn’t want to live his last moments in total despair, but there was no help for the dense and dark responsibility that would serve as his shroud. Thirty-six people, men and women who had been his family for the last four years, trapped and asphyxiated. And all because of him, because of his stubborn inability to accept the truth. Because he hadn’t opened his eyes until it was too late.

Behind him, the doors to the lift swished open, and there stood the unwelcome passenger, phaser in hand. A personal oxygen filter was fixed across his lower face, but Casden could see the glitter of false apology in his dark blue eyes.

From the station—

“I’m sorry about this,” he said, and before Casden could think twice, he was rushing at the bastard, cold and dizzy and determined to take down the man responsible for the nightmare, his own life hardly worth saving in the face of what he’d helped create.

Chapter One

Captain’s Log, Stardate 5462.1:

Having completed our survey to the edge of the Federation’s recently incorporated Lantaru sector, we are now turning back toward more populated space. A Federation science summit is being held on Deep Space Station M-20 in two days; senior science officers and engineers from most of the ships in the quadrant are expected to attend, as well as several top Federation research scientists.

Dr. McCoy and the medical staff have begun their biannual physical workups for each crew member; I expect his initial report within the week.

* * *

On the bridge of the Enterprise, Captain James T. Kirk sat back in his chair, glad that he wouldn’t have to endure yet another physical. It often seemed as if he had to go the rounds with McCoy’s machinery every month or so, and as often as he ended up getting knocked around, being prodded and poked one more time wasn’t high on his list of things to do. He’d been thoroughly checked out after the trouble with the interphase phenomenon and the Tholians only a few weeks ago, and Bones had declared him fit as a fiddle.

Well, except for being overworked, Kirk thought, gazing absently at the stars coursing by on the main viewscreen, passing at a leisurely warp four. Undoubtedly one of the constants in McCoy’s reports—Bones loved to point out that the captain of the Enterprise needed to schedule himself a real vacation, or something dramatic and terrible might happen. Kirk liked to point out in turn that the ship’s chief medical officer hadn’t taken one in just as long, but Bones somehow managed to avoid hearing that part. The man was as stubborn as stubborn got.

Kirk smiled, just a little; one had to admire his tenacity, anyway. The science conference might allow both of them a break, at least for a couple of days; the main theme was to be the Federation’s development of alternative power sources, much better suited to Spock or Scotty’s area of interest than either of their own. Even at warp four they’d arrive a half day early, and technically, there would be nothing they had to do . . . however Bones felt about it, Kirk knew that a change of scenery would do him some good, not to mention a few reunions he was looking forward to—he wasn’t sure about Commodore Mendez, but thought that Bob Wesley’s ship was in the sector, and had heard that Gage Darres was assigned to M-20. It would be nice to see a few familiar faces—

“Captain, I’m picking up a signal from a Federation ship . . .”

Behind him, Lieutenant Uhura’s voice was as cool and collected as always, but with a thread of tension that snapped Kirk out of his meandering reverie.

“ . . . it’s the automated distress call of the U.S.S. Sphinx, condition red, disaster status,” Uhura said, and Kirk was on his feet. At his station, Spock’s hands were already moving, adjusting the ship’s sensors to seek out the vessel.

The automated disaster signal only kicked in when there was no one to stop it from kicking in. Kirk quickly ran through the most likely possibilities as Uhu

ra accessed stats, not liking any of them— Plague. Hostile takeover. Antimatter breach. Another damned planet killer . . .

“U.S.S. Sphinx, Centaurus-class starship, Captain Jack Casden commanding,” Uhura said.

“How many aboard?” Kirk asked, unable to deny a small measure of relief. Centaurus vessels were primarily used for either scout or ambassadorial transport, occasionally as scientific surveyors, though not as processors; they were built for speed, and were among the smallest of the Federation’s warp-capable ships. A Centaurus-class couldn’t carry more than a hundred people.

“Crew list is thirty-seven, sir.”

“Speed and bearing?” Kirk asked, stepping forward to look over Sulu’s shoulder.

“It’s traveling at . . . warp seven, from the Lantaru sector,” Sulu said. “Headed 221 mark 35.”

Damn. It was more or less aimed at a cluster of Federation civilian colonies in the Ramatis system, less than an hour away at that speed.

“Can you open a channel?” Kirk asked, turning to look at Uhura. She held her earpiece in place with one hand, deftly manipulating her station’s receptors with the other.

“Negative, sir. Subspace arrays aren’t receiving.” Bent over his station, Spock read off information from his console. “I’m picking up evidence of expelled warp plasma and debris trailing behind the ship.” Spock straightened, turning to face him. “Captain, the Sphinx is in an increasing acceleration pattern. It is now traveling at warp eight, and will reach warp nine in three minutes, twenty-two seconds at its current rate of increase.”

The Centaurus-class was made to be fast, but not that fast. She was damaged and dangerously out of control. Without knowing the status of the crew, they couldn’t afford to risk damaging the ship any further—but they also couldn’t let it get much closer to the heavily populated Ramatis system. She’d blow up before she reached it, but God only knew what was on board.

Kirk stepped to his chair, aware that he also couldn’t afford to waste time considering the possibilities. It had been less than a minute since Uhura had reported the distress signal, but allowing another moment to pass without acting could mean death for Captain Casden and the people on his ship. If they were even alive; there was no way to scan for life signs without getting closer.

We have to get them out of warp, now. A dozen half-formed thoughts darted through his deliberation before one evolved into an idea.

“Mr. Spock, assuming we can match their velocity, would it be possible to use the tractor beam to slow them down?” Kirk asked.

“It’s possible, but it would have to be an exact match,” Spock said. “Even a slight variance—”

“Mr. Chekov, lay in a parallel course,” Kirk said, having heard all he needed to hear. It was a plan, simple but better than none at all, and if anyone could pull it off, his people could. “Mr. Spock, Mr. Sulu, I want you to coordinate with Mr. Scott, we’re going to try and ease her out of subspace. Lieutenant, keep trying to raise them.”

Kirk sat down as he spoke, barely hearing the acknowledgments around him, already hitting the chair’s com with his right fist.

“Kirk to engineering. Scotty, we’ve got a situation.”

* * *

“You want me to what?”

Standing next to the wall com with one hand on the switch, Scotty felt the too-familiar knot of anxiety and disbelief hit his gut and take hold, the captain’s urgent explanation still ringing in his ears. Good Lord, what did he think the Enterprise was made out of, neutronium?

“You heard me. Spock’s sending the numbers down now, and helm is standing by.”

Scotty shook his head, the pulsing lights of the reaction chamber making his shadow spin at his feet. “Captain, I can get her up to speed, but there’s no way to maintain it, not if you mean to use the tractor beam to—”

“Yes, I know, it’s impossible,” Kirk snapped.

“And the longer you wait, the worse it’s going to get. Do whatever it takes, Mr. Scott, but do it now.”

“Aye, sir, Scott out,” Scotty said, turning to look at Grant and Washburn, seeing the same pained concern on their faces that he knew was on his own. It was just the three of them in main engineering, had been since lunch. Tam and Dixon were running diagnostics on the impulse drive and Celaux wasn’t coming on for another half hour.

“You heard him, lads. Mr. Washburn, line up Mr. Spock’s ratios and plug them in, then sit on the reaction chamber, watch for flux. And call in Celaux when you’re done, put her on overrides and secondaries.”

Scotty strode toward the warp-engine monitors deciding what they could spare, talking to Grant over his shoulder. “We’re going to siphon from the phaser-bank reserves for the tractor beam. Get the transfer conduits primed and stand by, I’m going to see what I can do with the shields—”

“Sir, we’re set to match,” Washburn said. “They’re at . . . eight-seven-four now.”

“Distance from us?”

“61.280 billion kilometers and closing.”

“Intersection?”

Washburn hesitated. “Uh . . . seventy-two million kilometers.”

“Tell helm to set to mark at . . . eight-eight and a half,” Scotty said, wincing inwardly, “and let Mr. Spock do the fine-tuning, we’ve got enough to do down here without hair-splitting.” The bridge crew would have to be on their game, and to the millisecond; in a crunch, the Enterprise could reach ninefive without sustaining serious injury, but not for any sustained period of time, a certainly not with a beam on. Not unless Scotty wanted to cut life-support and AG, which he did not—and success or no, there wasn’t going to be enough power for a second chance to catch the runaway. The captain could demand more power nine ways to Sunday, it wouldn’t make a bit of difference.

Lieutenant Uhura’s melodic voice floated hollowly through the chamber, a shipwide alert to secure positions. Scotty ignored it, figuring and entering a low-constant shield density into the boards, a part of him praying for the poor Sphinx and her crew, a part of him counting them lucky, indeed. If any ship in the galaxy could save her, surely it was the Enterprise.

* * *

“In twenty seconds, Mr. Sulu,” Mr. Spock intoned.

Hikaru Sulu’s fingers hovered over the warp-drive controls, watching science’s readings for the runaway ship on his console, listening as Mr. Spock began to count down. Engineering said the Enterprise would be ready when the Sphinx reached high eight, 8.8550 to be exact. Rick Washburn and Mr. Spock had fed the numbers to Chekov, who had adjusted course before sending it on to helm—and although he knew he could trust the mathematics, it made Sulu nervous not to have time to go over their calculations. This was going to be one tricky bit of flying.

“Sixteen . . . fifteen . . .”

They would be jumping to match warp just before the Sphinx passed them by, and although Sulu could easily slow the Enterprise down to fly alongside the runaway, having to speed up at all would throw the projections out of whack. Even without Mr. Scott’s dire warnings, Sulu knew that the Enterprise’s entire energy output would be fully engaged—and since he would be piloting, he had to be as close to perfect as was possible.

“Eleven . . . ten . . .”

A lock of hair fell across his forehead, but he barely noticed, his full concentration on the task in front of him; he heard nothing but Mr. Spock’s comfortingly bland voice, saw nothing but the dropping numbers on his screen, indicating the rapidly closing distance between the two ships. Mr. Scott would provide the power, Mr. Spock would handle the tractor beam, and the captain would give the commands—but it was up to him to fly straight and true, to bring them alongside the ailing ship so that they might save her from certain destruction.

“Three . . . two . . . one. Engage warp now, Mr. Sulu.”

Sulu lightly tapped the switches as Mr. Spock spoke the word “engage,” and the Enterprise surged forward, the stars blurring, the low rumbling of the massive engines rising through the walls and floor of the bridge.

A h

alf second later, the Sphinx leapt on to the main viewing screen, and Sulu felt a burst of pride, the small ship less than twelve kilometers to port and only seven kilometers behind. He eased the Enterprise toward her, watching his console rather than the viewscreen—

—and felt his pride dissolve as he realized what was happening, even as Mr. Spock reported it to the captain. A glance at the screen confirmed it, the obviously impaired ship spewing a misty, ragged cloud of escaping gases, barely visible as it was torn away by warp—but it was just enough to disturb the Sphinx’s velocity constant. Sulu held his course and waited for instruction, wondering if Mr. Scott would be able to compensate, knowing already that it was practically impossible.

And we can’t hold a tractor beam in warp without a precise velocity match. At best, the effort would be useless . . . and at worst, the beam could act like a battering ram, violently pushing the Sphinx away and causing more damage.

“In addition to their damaged core, it appears that their oxygen stores have been ruptured. The continued expulsion of gases and fuel is causing an erratic and unascertainable flight pattern,” Mr. Spock said. “The possibility of achieving an exact parallel to its course is no longer a viable option.”

Chapter Two

The captain stared at the viewscreen for a beat, frowning, then half-turned in his chair to look at Spock.

“Life signs?” he asked.

Spock glanced at his console once more, but there had been no change in the few seconds since he’d last checked.

“Readings are uncertain. I’m detecting several heat signatures, but they may be caused by mechanical overload. Life-support appears to be inactive.”

“We have to stop that ship, Mr. Spock. What can we do?”

The captain’s frustration was clear in his voice, but Spock had no immediate answer, not unless he interpreted the question literally—which was not, of course, what Captain Kirk wanted.

The Umbrella Conspiracy

The Umbrella Conspiracy Zero Hour

Zero Hour Caliban Cove

Caliban Cove Code: Veronica

Code: Veronica Nemesis

Nemesis Underworld

Underworld The Summer Man

The Summer Man Virus

Virus Shadow of the Tomb Raider--Path of the Apocalypse

Shadow of the Tomb Raider--Path of the Apocalypse Unity

Unity Rising Son

Rising Son Resident Evil: Underworld

Resident Evil: Underworld Resident Evil – Caliban Cove

Resident Evil – Caliban Cove Resident Evil – Nemesis

Resident Evil – Nemesis Resident Evil – City of the Dead

Resident Evil – City of the Dead Resident Evil – Underworld

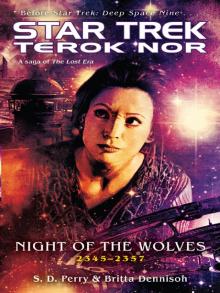

Resident Evil – Underworld Star Trek: Terok Nor 03: Dawn of the Eagles

Star Trek: Terok Nor 03: Dawn of the Eagles Twist of Faith

Twist of Faith Star Trek: Inception

Star Trek: Inception Cloak

Cloak Resident Evil

Resident Evil Star Trek - TOS - Section 31 - Cloak

Star Trek - TOS - Section 31 - Cloak Star Trek: Terok Nor 02: Night of the Wolves

Star Trek: Terok Nor 02: Night of the Wolves